Fashion and The YeeHaw Agenda

For decades, the American cowboy has existed as a fixed cultural image: a white man on horseback, framed by open land and dust-filled sunsets. Cinema, textbooks and mainstream fashion have reinforced this figure so consistently that it feels almost inseparable from American identity itself.

But this image is incomplete.

Historical research suggests that one out of every four cowboys in the American West was Black. And yet, their presence has been systematically minimized, romanticized out of existence, or omitted entirely. The rise of the Yeehaw Agenda is not simply a fashion revival or a social media trend, it is part of a broader cultural correction.

To understand why these matters, we need to revisit the origins of the cowboy myth.

The Cowboy and the Construction of American Identity

The cowboy has long symbolized independence, masculinity and frontier resilience. He embodies a national fantasy, self-reliant, fearless, untamed. But the West was never racially homogeneous.

After the Civil War, many formerly enslaved African Americans became cowboys. Their expertise in livestock management and ranch labor, developed under forced plantation work, made them essential to the cattle industry. When emancipation reshaped the Southern labor system, ranch owners relied heavily on these men to sustain their operations.

For many Black men in post-war America, cowboy life was not a romantic adventure but one of the few available economic opportunities. It offered relative mobility and skill recognition, even within a deeply segregated society.

Yet despite their significance, Black cowboys were denied visibility in the dominant narrative. Leadership positions remained largely inaccessible. Segregation restricted their movement in public spaces. And over time, Western iconography became overwhelmingly white.

The myth persisted. The reality was edited.

Rodeos and Institutional Exclusion

As cattle ranching declined, rodeos emerged as a performative extension of cowboy culture, spaces where skill became spectacle. These events solidified the cowboy as an entertainment archetype.

However, Black cowboys were frequently excluded from mainstream competitions. In some cases, they were permitted to perform only before official events began; in others, they were banned altogether under discriminatory justifications. The idea that a Black rider might “devalue” livestock reveals how racism was embedded even in economic reasoning.

In response, Black cowboys created independent platforms such as the Cowboys of Colour Rodeo. These were not merely parallel events, they were acts of cultural preservation and assertion.

They signalled continuity: we are not a deviation from cowboy culture; we are part of its foundation.

Trail Rides: Celebration as Historical Memory

Beyond rodeos, Black communities-maintained cowboy traditions through trail rides, gatherings that blend horsemanship, music, food and collective remembrance. In Texas and Louisiana especially, these rides function as both celebration and archive.

Participants ride through towns wearing boots and hats, accompanied by zydeco rhythms, country influences and communal meals. The atmosphere is festive, yet deeply symbolic. It reconnects present-day riders with ancestral histories that were marginalized in mainstream accounts.

Even these celebrations have faced scrutiny and regulation in ways that echo broader patterns of racialized control. Visibility has often been met with resistance.

And yet, the rides continue.

From Protest to Cultural Reclamation

The renewed visibility of Black cowboys in recent years cannot be separated from wider political movements. The rise of Black Lives Matter intensified national conversations about systemic racism, historical erasure and representation.

During protests following the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, groups of Black cowboys appeared on horseback wearing shirts that read “Black Cowboys Matter.” The imagery was powerful: the quintessential symbol of the American frontier now aligned with demands for racial justice.

It was both aesthetic and political.

The horse became a moving statement.

A reclamation of space.

A reminder of historical presence.

The Yeehaw Agenda and the Power of social media

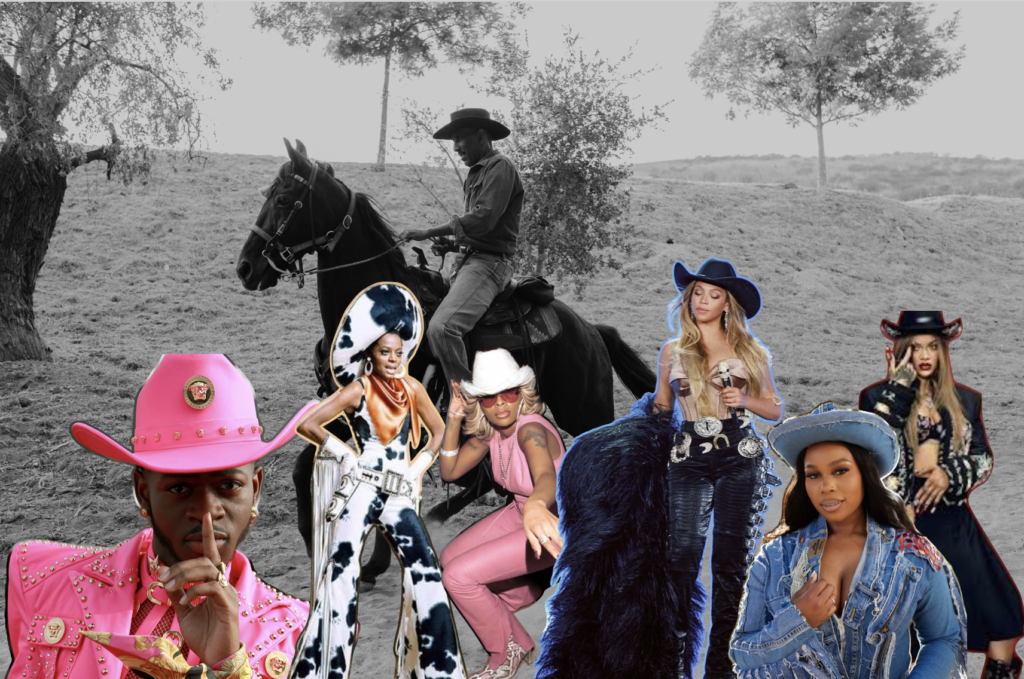

In 2018, the term “Yeehaw Agenda” was popularized to describe the growing movement highlighting Black Western identity. Soon after, Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” blurred genre boundaries between country and trap, igniting both cultural celebration and controversy. The song’s initial removal from the country charts sparked debate about race, authenticity and who gets to define “country.”

Social media amplified the moment. Hashtags, styling challenges and viral threads circulated Western aesthetics through a contemporary lens. The cowboy hat became more than an accessory; it became a statement of inclusion.

In this sense, digital platforms functioned as modern-day streets, gathering spaces where narratives could be contested and rewritten in real time.

Fashion as Cultural Correction

As the movement gained visibility, fashion responded. Designers, musicians and filmmakers began centering Black Western aesthetics in their work. Runways incorporated reinterpreted cowboy silhouettes. Artists performed in Western-inspired looks that consciously referenced historical presence.

Films like The Harder They Fall reimagined the Western genre by foregrounding Black outlaw stories long excluded from cinematic canon.

Western fashion, once nostalgic and romanticized, became layered with new meaning. It was no longer simply about Americana , it was about authorship.

Who gets to wear the myth?

Who gets to define the narrative?

Reframing the American Silhouette

Today, the cowboy remains an enduring symbol, boots, hat, denim, leather. But the silhouette now carries expanded meaning. It represents historical revision, cultural resilience and the refusal to be erased.

Fashion has always been a site where identity is negotiated. The Western aesthetic, filtered through the lens of the Yeehaw Agenda, reminds us that style is inseparable from history.

And sometimes the most radical act is not reinvention, but recognition.

Black cowboys were never absent.

They were simply edited out.

The Western Trend… But Make It 2026

Fast forward to now, and Western is everywhere again — but it feels different.

We’re seeing:

– Cowboy boots styled with minimalist tailoring in London and Paris

– Denim-on-denim elevated with luxury proportions

– Belt buckles as statement jewellery

– Leather chaps reinterpreted for runways

– Western hats styled with sleek city silhouettes

It’s no longer about dressing like you’re going to a ranch. It’s about referencing a symbol and rewriting its meaning.

The “cowboy core” resurgence across TikTok and runways isn’t just aesthetic recycling,

it’s layered with cultural context. Whether consciously or not, the mainstream revival of Western style exists in a world where the Yeehaw Agenda has already shifted the narrative.

Now when we see a cowboy hat, it doesn’t automatically code as white Americana. The image has been expanded.

And fashion, as always, absorbed the shift.

Trends rarely exist in isolation. They’re reflections of deeper cultural conversations. The return of Western style coincides with a broader reckoning around identity, authorship and representation.

Who gets to wear the myth?

Who gets to profit from it?

Who gets remembered?